MOHD RASFAN/AFP via Getty Images

In Southeast Asia, the durian is the undisputed king of fruit. Crack open its thorny green husk, and you'll find several yellow or red nuggets of custard-like pulp that melts in your mouth.

The smell, though, is divisive. Durians are so pungent that Anthony Bourdain once said they make your breath smell like "French-kissing your dead grandmother," and food writer Richard Sterling opined that "its odor is best described as pig-s–t, turpentine, and onions, garnished with a gym sock."

The fruit is so smelly it's banned on public transport in Thailand, Japan, Singapore, and Hong Kong.

Still, durians are a special treat in Asian households, and, at as much as $13 a pound, they're not cheap. They're also the subject of an increasingly bitter year-long battle between Malaysian farmers who cultivate premium durian trees and a government-backed consortium that's trying to cash in on the beloved fruit.

At the center of this dispute is one specific breed of durian: the Musang King. It's been called gold that grows on trees, and a single tree can earn farmers up to $1,000 a year.

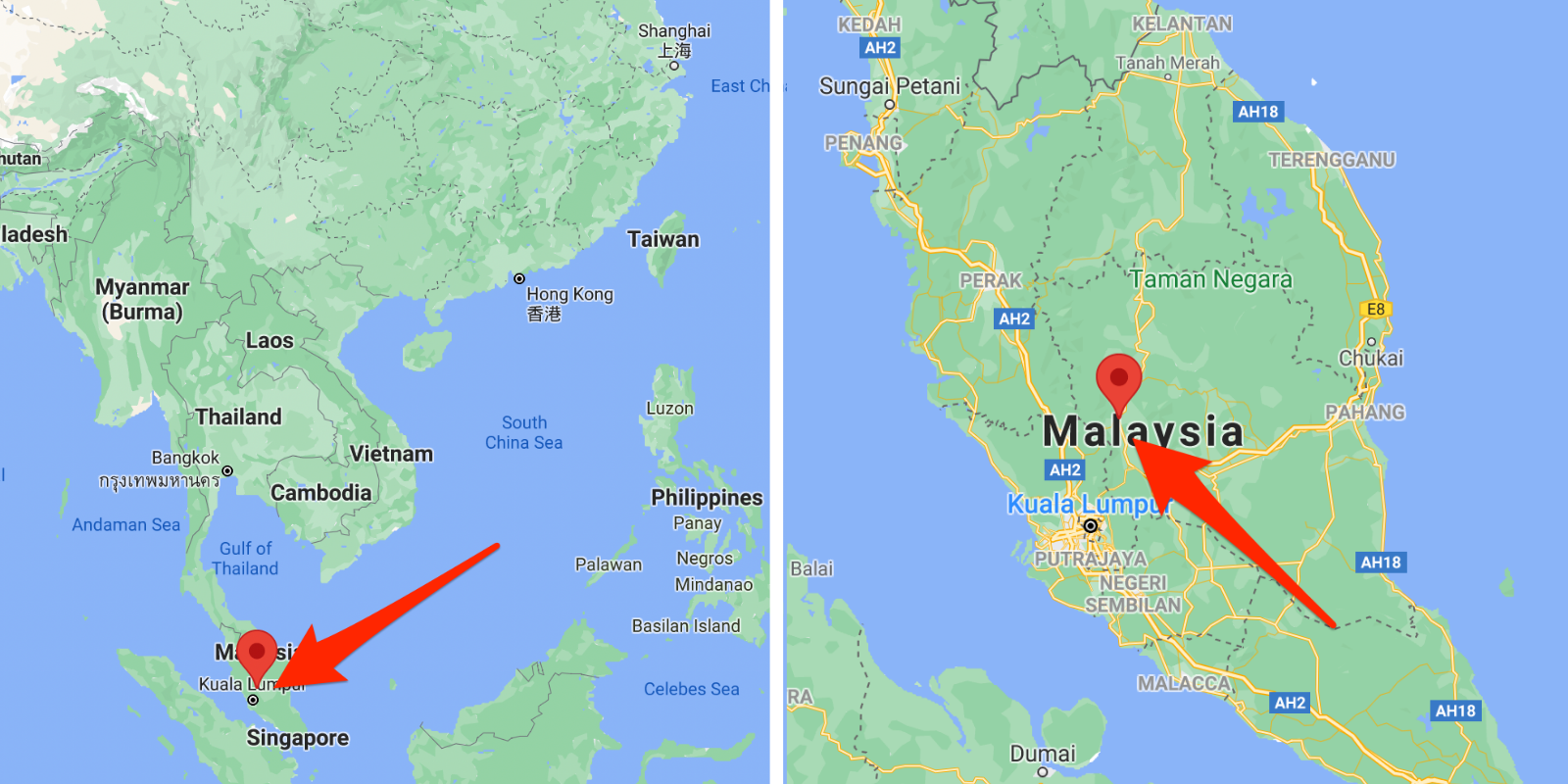

Most of the world's Musang King durians come from Raub, an old mining township of 100,000 people that has become the "durian capital of Malaysia" after farmers discovered its soil and climate were perfect for growing the fruit.

Google Maps

Tan Wai Kiat's family has been growing Musang King on a plantation in Raub for 20 years. Just like with wine, trees that age longer produce better fruit. The average tree has to mature for up to 10 years before it starts bearing industry-standard Musang King.

Tan's crop used to bring in around $46,000 a year, a tidy sum considering the country's median annual income is less than $6,000.

But all that's left of his farm now are logs and mud, he told Insider. In mid July, the state forestry department finished chopping down 15,000 durian trees, including the entirety of Tan's 13-acre plantation.

Farmers like Tan believe the destruction of the 15,000 trees is meant as a warning to other durian growers, since the area cleared only spans around 250 of the total 5,537 acres involved in the dispute.

When Tan heard that his plantation was being destroyed, he and other affected farmers rushed there to negotiate with on-site officials, he told Insider. A video of the confrontation shows that tensions were high. State authorities had sealed off the area, and the group was arrested on charges of trespassing and detained for 48 hours. Days later, Tan's entire farm was wiped out.

"I don't know what to think. I don't know what I'm supposed to do. It feels like there is no rule of law in this country," he said.

Save Musang King Alliance

The battle around Raub's Musang King comes as demand for the fruit has been exploding in popularity in China.

In 2020, a durian festival in China sold out $15 million worth of Musang King in 60 minutes, and flocks of Chinese tourists have been paying to visit Raub's plantations.

Durian is now China's No. 1 fruit import by value, and the country bought $2.3 billion of it last year. China has historically brought in durians from Thailand, which holds an exclusive trade agreement with Beijing for fresh durians, but a 2019 deal with Malaysia to sell frozen durian has seen Chinese interest in Malaysia's Musang King varietal skyrocket.

Julie Gerstein / Insider

The Musang King craze has been around for at least 20 years in Singapore, said durian expert Charles Phua, who owns a durian shop in the city and has been consulted by Michelin for guides on the fruit. It's the reason why people start lining up every morning in front of his shop during harvest season an hour before he opens. Prior to the pandemic, foreigners would fly into Singapore just to buy Musang King, he said.

The golden Musang King is the "most famous of them all" because of its strong bittersweet taste and unrivaled creaminess, said Phua. At his stall, one pound of his best Musang King goes for $13 a pound.

Charles Phua, Dr Durian

The great durian land grab

As interest in durian cultivation has grown, so has interference from Raub's state government, say Musang King farmers.

Most of the Musang King farms in Raub - like Tan's - are built on government-owned land and are technically being run without permission from state authorities.

Farmers say they have been trying to legalize their farms for years. Tan said his family have applied for a land title multiple times since 2011. His latest application was in 2015, according to documents seen by Insider, and is still pending.

Even so, Tan's family had farmed Musang King peacefully and without interference from the state, he said - until now. "They just saw that there are profits, and now they want to come in and contest the rights to the land," Tan said.

That's where Royal Pahang Durian Group (RPDG) comes into play.

The association, which was launched around 2017, is partnered with the state agricultural department. Its shareholders include the country's royal family - the sultan's daughter is the chairperson of the board. In June 2020, the state government awarded the RPDG more than 5,500 acres of Musang King soil.

The problem is that the land was already host to roughly 1,000 Musang King farmers.

RPDG told farmers it would lease them back the land - the same land on which those very farmers had already been running plantations for decades - for a one-time fee of around $1,400 an acre.

But the leased land comes with strings.

The farmers are required to sell their durian to the consortium at a fixed rate of about $4.30 per pound. This price is well below market rate for Musang King, which can reach as high as $6.80 per pound, the farmers said. On top of all that, the consortium charges the farmers an additional $1 per pound of Musang King, which it said would go toward miscellaneous fees and state land taxes.

The association said the scheme was put in place to protect the Musang King industry from foreign players and that farmers would make large profits under its plan.

In response, 204 farmers formed a group called the Save Musang King Alliance, and said the proposal was exploitative and would turn them into "modern slaves." The scheme is not unlike share-cropping arrangements that were offered to former slaves in the South after the Civil War.

These are the trees that I put my tears and sweat into for years.

Consider Tan's now-destroyed farm as an example. If the lease were to be applied to Tan's farm, it would have cost him 40% of his total $46,000 yearly revenue. He said he used to spend nearly a third of his revenue on labor, fertilizer, and pest control every year. If those expenses were combined with the new land levies and the lower market price, he would make essentially nothing, he said.

Chiang Heng Mun, another farmer whose 20-acre plantation was completely cleared this month, said the state forestry department and consortium are creating a culture of fear among the Musang King growers.

"These are the trees that I put my tears and sweat into for years," he told Insider. Chiang, the sole breadwinner for his family, lives with his wife, parents, and two kids in their rural house near Raub. His family has been durian farmers in the area for 20 years.

"We have been trying to meet with them to work things out, but they don't respond. We just want fair treatment, because we have been working here for many years," he told Insider.

The Pahang Agricultural Department declined to respond to Insider's request for comment, citing its ongoing legal dispute with the farmers. The RPDG and the Pahang State Forestry Department did not immediately respond to Insider's requests for comment.

MOHD RASFAN/AFP via Getty Images

'How can my family survive the pandemic?'

The farmer's alliance plans to wage its legal battle on two fronts.

Its main objective is to question why the land was leased to the consortium, said Chow Yu Hui, a Malaysian state assemblyman and opposition politician who rallied the farmers last year.

"We have many documents to prove that these farmers have been working here for 30, 40 years, building the brand of the Musang King," said Chow. "Why not lease the land to them?"

The alliance is also arguing that the 15,000 trees destroyed this month were on land that's protected by a superior court. The farmers managed to secure a stay of eviction in January in the Court of Appeal, which allowed them to return to their plantations and work until their case is reviewed. The court order, seen by Insider, includes protection against the destruction of their Musang King trees.

Meanwhile, the state forestry department says the durian trees cleared were not covered in the court order, a claim that Chow and the farmers deny.

However, the dispute is difficult for the farmers to contest because the exact boundaries of the land sold to RPDG have not been publicly disclosed, Chow told Insider.

The farmer's alliance is now looking to create a proposal with the state government that will let them sell their durians at free-market value and be treated as equal partners.

Even if they succeed, there is not much of a future left for farmers like Tan and Chiang, now that their plantations are gone.

Tan plans to help out on other farms to feed his extended family of 10, who all live in a one-story village house. He and his brother, whose durian plantation was also destroyed this month, were the family's only sources of income.

Save Musang King Alliance

Chiang said he legally owns several acres apart from his destroyed plantation, where he plants other fruit like bananas. But without his Musang King trees, he doubts the money will be close to what his family needs to live off of. He's looking for odd jobs, but said he can barely find work now.

"I have no hopes, no dreams anymore," Chiang said. "When they chop down all of my trees, how can my family survive the pandemic?"